Angkor Wat Temple Guides

Site and Plan

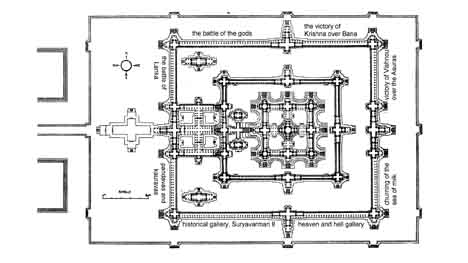

Angkor Wat is a Hindu-Buddhist temple complex. Located on a site measuring 162.6 ha (1,626,000 m2; 402 acres) within the ancient Khmer capital city of Angkor, it is considered as the largest religious structure in the world by Guinness World Records.

Angkor Wat is a unique combination of the temple mountain (the standard design for the empire’s state temples) and the later plan of concentric galleries, most of which were

originally derived from religious beliefs of Hinduism. The construction of Angkor Wat suggests that there was a celestial significance with certain features of the temple. This is observed in the temple’s east–west orientation, and lines of sight from terraces within the temple that show specific towers to be at the precise location of the solstice at sunrise. The Angkor Wat temple’s main tower aligns with the morning sun of the spring equinox. The temple is a representation of Mount Meru, the home of the gods according to Hindu mythology: the central quincunx of towers symbolise the five peaks of the mountain, and the walls and moat symbolise the surrounding mountain ranges and ocean. Access to the upper areas of the temple was progressively more exclusive, with the laity being admitted only to the lowest level.

Unlike most Khmer temples, Angkor Wat is oriented to the west rather than the east. This has led scholars including Maurice Glaize and George Coedès to hypothesize that Suryavarman intended it to serve as his funerary temple. Further evidence for this view is provided by the bas-reliefs, which proceed in a counter-clockwise direction—prasavya in Hindu terminology—as this is the reverse of the normal order. Rituals take place in reverse order during Brahminic funeral services. Archaeologist Charles Higham also describes a container that may have been a funerary jar that was recovered from the central tower. It has been nominated by some as the greatest expenditure of energy on the disposal of a corpse. Freeman and Jacques, however, note that several other temples of Angkor depart from the typical eastern orientation, and suggest that Angkor Wat’s alignment was due to its dedication to Vishnu, who was associated with the west.

Drawing on the temple’s alignment and dimensions, and on the content and arrangement of the bas-reliefs, researcher Eleanor Mannikka argues that the structure represents a claimed new era of peace under King Suryavarman II: “as the measurements of solar and lunar time cycles were built into the sacred space of Angkor Wat, this divine mandate to rule was anchored to consecrated chambers and corridors meant to perpetuate the king’s power and to honour and placate the deities manifest in the heavens above. Mannikka’s suggestions have been received with a mixture of interest and scepticism in academic circles. She distances herself from the speculations of others, such as Graham Hancock, that Angkor Wat is part of a representation of the constellation Draco. The oldest surviving plan of Angkor Wat dates to 1715 and is credited to Fujiwara Tadayoshi. The plan is stored in the Suifu Meitoku-kai Shokokan Museum in Mito, Japan.

Style

Angkor Wat is the prime example of the classical style of Khmer architecture—the Angkor Wat style—to which it has given its name. Architecturally, the elements characteristic of the style include the ogival, redented towers shaped like lotus buds; half-galleries to broaden passageways; axial galleries connecting enclosures; and the cruciform terraces which appear along the main axis of the temple. Typical decorative elements are devatas (or apsaras), bas-reliefs, pediments, extensive garlands and narrative scenes. The statuary of Angkor Wat is

considered conservative, being more static and less graceful than earlier work. Other elements of the design have been destroyed by looting and the passage of time, including gilded stucco on the towers, gilding on some figures on the bas-reliefs, and wooden ceiling panels and doors.

The temple has drawn praise for the harmony of its design. According to Maurice Glaize, the temple “attains a classic perfection by the restrained monumentality of its finely balanced elements and the precise arrangement of its proportions. It is a work of power, unity, and style. Architect Jacques Dumarçay believes the layout of Angkor Wat borrows Chinese influence in its system of galleries which join at right angles to form courtyards. However, the axial pattern embedded in the plan of Angkor Wat may be derived from Southeast Asian cosmology in combination with the mandala represented by the main temple.

France adopted Cambodia as a protectorate on 11 August 1863 partly due to the artistic legacy of Angkor Wat and other Khmer monuments in the Angkor region and invaded Siam. This quickly led to Cambodia reclaiming lands in the northwestern corner of the country including Siem Reap, Battambang, and Sisophon which were under Siamese rule from 1795 to 1907. Following excavations at the site, there were no ordinary dwellings or houses or other signs of settlement such as cooking utensils, weapons, or items of clothing usually found at ancient sites.

Features

Outer Enclosure

The temple complex is surrounded by an outer wall, 1,024 m (3,360 ft) by 802 m (2,631 ft) and 4.5 m (15 ft) high. It is encircled by a 30 m (98 ft) apron of open ground and a moat 190 m (620 ft) wide and over 5 km (3.1 mi) in perimeter. The moat extends 1.5 km (0.93 mi) from east to west and 1.3 km (0.81 mi) from north to south. Access to the temple is by an earth bank to the east and a sandstone causeway to the west; the latter, the main entrance, is a later addition, possibly replacing a wooden bridge. There are gopuras at each of the cardinal points with the western one being the largest and consisting of three partially ruined towers. Glaize notes that this gopura both hides and echoes the form of the temple proper.

Under the southern tower is a statue known as Ta Reach, originally an eight-armed statue of Vishnu that may have occupied the temple’s central shrine. Galleries run between the towers and two further entrances on either side of the gopura often referred to as “elephant gates”, as they are large enough to admit those animals. These galleries have square pillars on the outer (west) side and a closed wall on the inner (east) side. The ceiling between the pillars is decorated with lotus rosettes. The west face of the wall is decorated with dancing figures and the east face of the wall consists of windows with balusters, decorated with dancing figures, animals and devatas.

The outer wall encloses a space of 203 acres (82 ha), which besides the temple proper was originally occupied by people from the city and the royal palace to the north of the temple. Similar to other secular buildings of Angkor, these were built of perishable materials rather than of stone, so nothing remains of them except the outline of some of the streets with most of the area now covered by vegetation. A 350 m (1,150 ft) causeway connects the western gopura to the temple proper, with naga shaped balustrades and six sets of steps leading down to the outside on either side. Each side also features a library with entrances at each cardinal point, in front of the third set of stairs from the entrance, and a pond between the library and the temple itself. The ponds are later additions to the design, as is the cruciform terrace guarded by lions connecting the causeway to the central structure.

Central Structure

The temple stands on a raised terrace within the walled enclosure. It is made of three rectangular galleries rising to a central tower, each level higher than the last. The two inner galleries each have four large towers at their ordinal corners (that is, North-west, North-east, South-east, and South-west) surrounding a higher fifth tower. This pattern is sometimes called a quincunx and is believed to represent the mountains of Meru. Because the temple faces west, the features are set back towards the east, leaving more space to be filled in each enclosure and gallery on the west side; for the same reason, the west-facing steps are shallower than those on the other sides.

Mannikka interprets the galleries as being dedicated to the king, Brahma, the moon, and Vishnu. Each gallery has a gopura with the outer gallery measuring 187 m (614 ft) by 215 m (705 ft), with pavilions at the corners. The gallery is open to the outside of the temple, with columned half-galleries extending and buttressing the structure. Connecting the outer gallery to the second enclosure on the west side is a cruciform cloister called Preah Poan (meaning “The Thousand Buddhas” gallery). Buddha images were left in the cloister by pilgrims over the centuries, although most have now been removed. This area has many inscriptions relating to the good deeds of pilgrims, most written in Khmer but others in Burmese and Japanese. The four small courtyards marked out by the cloister may originally have been filled with water. North and south of the cloister are libraries.

Beyond, the second and inner galleries are connected to two flanking libraries by another cruciform terrace, again a later addition. From the second level upwards, devata images are abound on the walls, singly or in groups of up to four. The second-level enclosure is 100 m (330 ft) by 115 m (377 ft), and may originally have been flooded to represent the ocean around Mount Meru. Three sets of steps on each side lead up to the corner towers and gopuras of the inner gallery. The steep stairways may represent the difficulty of ascending to the kingdom of the gods. This inner gallery, called the Bakan, is a 60 m (200 ft) square with axial galleries connecting each gopura with the central shrine and subsidiary shrines located below the corner towers.

The roofings of the galleries are decorated with the motif of the body of a snake ending in the heads of lions or garudas. Carved lintels and pediments decorate the entrances to the galleries and the shrines. The tower above the central shrine rises 43 m (141 ft) to a height of 65 m (213 ft) above the ground; unlike those of previous temple mountains, the central tower is raised above the surrounding four. The shrine itself, originally occupied by a statue of Vishnu and open on each side, was walled in when the temple was converted to Theravada Buddhism, the new walls featuring standing Buddhas. In 1934, the conservator George Trouvé excavated the pit beneath the central shrine: filled with sand and water it had already been robbed of its treasure, but he did find a sacred foundation deposit of gold leaf two metres above ground level.

Decoration

Integrated with the architecture of the building, one of the causes for its fame is Angkor Wat’s extensive decoration, which predominantly takes the form of bas-relief friezes. The inner walls of the outer gallery bear a series of large-scale scenes mainly depicting episodes from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Higham has called these “the greatest known linear arrangement of stone carving”. From the north-west corner anti-clockwise, the western gallery shows the Battle of Lanka from the Ramayana, in which Rama defeats Ravana; and the Kurukshetra War from the Mahabharata, depicting the mutual annihilation of the Kaurava and Pandava armies. On the southern gallery, the only historical scene, a procession of Suryavarman II is depicted along with the 32 hells and 37 heavens of Hinduism.

On the eastern gallery is one of the most celebrated scenes, the Churning of the Sea of Milk, showing 92 asuras and 88 devas using the serpent Vasuki to churn the sea of milk under Vishnu’s direction. Mannikka counts only 91 asuras and explains the asymmetrical numbers as representing the number of days from the winter solstice to the spring equinox, and from the equinox to the summer solstice. It is followed by reliefs showing Vishnu defeating asuras, which was a 16th-century addition. The northern gallery shows Krishna’s victory over Bana.

Angkor Wat is decorated with depictions of apsaras and devatas with more than 1,796 documented depictions of devatas in the research inventory. The architects also used small apsara images (30–40 cm or 12–16 in) as decorative motifs on pillars and walls. They incorporated larger devata images (full-body portraits measuring approximately 95–110 cm or 37–43 in) more prominently at every level of the temple from the entry pavilion to the tops of the high towers. In 1927, Sappho Marchal published a study cataloging the remarkable diversity of their hair, headdresses, garments, stance, jewellery, and decorative flowers depicted in the reliefs, which Marchal concluded were based on actual practices of the Angkor period.

Construction Techniques

By the 12th century, Khmer architects had become skilled and confident in the use of sandstone rather than brick or laterite as the main building material. Most of the visible areas are sandstone blocks, while laterite was used for the outer wall and hidden structural parts. The binding agent used to join the blocks is yet to be identified, although natural resins or slaked lime has been suggested. The monument was made of five to ten million sandstone blocks with a maximum weight of 1.5 tons each. The sandstone was quarried and transported from Mount Kulen, a quarry approximately 40 km (25 mi) northeast.

The route has been suggested to span 35 km (22 mi) along a canal towards Tonlé Sap lake, another 35 km (22 mi) crossing the lake, and finally 15 km (9 mi) against the current along Siem Reap River, making a total journey of 90 km (55 mi). In 2011, Etsuo Uchida and Ichita Shimoda of Waseda University in Tokyo discovered a shorter 35 km (22 mi) canal connecting Mount Kulen and Angkor Wat using satellite imagery and believe that the Khmer used this route instead.

Most of the surfaces, columns, lintels and roofs are carved with reliefs illustrating scenes from Indian literature including unicorns, griffins, winged dragons pulling chariots, as well as warriors following an elephant-mounted leader, and celestial dancing girls with elaborate hairstyles. The gallery wall is decorated with almost 1,000 m2 (11,000 sq ft) of bas reliefs. Holes on some of the Angkor walls indicate that they may have been decorated with bronze sheets which were highly prized in ancient times and were prime targets for robbers. Based on experiments, the labour force to quarry, transport, carve and install so much sandstone probably ran into the thousands including many highly skilled artisans. The skills required to carve these sculptures were developed hundreds of years earlier, as demonstrated by some artefacts that have been dated to the seventh century, before the Khmer came to power.